CPS News

Religion’s Sudden Decline, Revisited

Posted February 26, 2021. By Ronald Inglehart, Jon Miller, Michael Dennis, Stephanie Jwo, and Gergely Rosta

An article by Inglehart, “Giving Up on God: The Global Decline of Religion,” published in the September/October issue of Foreign Affairs contains errors that also appear in his book, Religion’s Sudden Decline: What’s Causing it, and What comes Next? (Oxford University Press, 2021). The original version of the 2017 U.S. data provided by NORC at the University of Chicago overstated the degree to which the importance of God had declined among the American public.

The purpose of this note is to alert World Values Survey (WVS) users of the error in the previously released version of the U.S. data, to indicate that a corrected version of the U.S. data is now included in the current WVS release file, and to discuss to origin of this error as a learning moment for future WVS data collection. This information has also been shared on the World Values Survey website. The AmeriSpeak panel service of the NORC is built on a national sample of households obtained from a national listing of residences maintained by the U.S. Post Office and uses a combination of online surveys and telephone interviews for households without Internet access or who prefer a telephone call. In recent years, an increasing number of respondents have completed the online survey using a smartphone. In the case of the 7th cycle WVS, the smartphone version of the survey included approximately 400 separate screens. We understand that few countries currently collect data from smartphones and we share the details of this experience to alert our colleagues to the complexities associated with the conversion of traditional online surveys into a smaller screen smartphone format.

In November, 2020, Gergely Rosta, the Hungarian Principal Investigator of the World Values Survey (WVS) detected anomalies in the data of the 2017 U.S. survey that he pointed out to the U.S. Principal Investigators Jon Miller and Ronald Inglehart. Miller and Inglehart asked NORC to examine its raw data and the relevant code to confirm the data. Jwo reviewed the raw data and code and found that there was a transmission error between for smartphone format and the larger online computer format in a small number of questions. In recent decades, online surveys frequently use matrix format questions, with the question wording on the left margin and the responses categories expressed in columns. This format is convenient for both question writers and respondents, but the smaller screen of a smartphone requires that each row be presented to the respondent as a separate screen. Code is written to convert these responses into a data storage format compatible with the online format. The error occurred in the conversion of the smartphone responses into the online format. Reflecting their long-standing commitment to high quality data collection, Jwo and her NORC colleagues did a thorough job of reviewing the code and data and making corrections. In the process, it was discovered that a very small number of cases – less than one percent – involved an incorrect missing data value and those errors were corrected at the same time.

The data originally received indicated that from 2007 to 2019, the American public showed the largest decline of any country for which data were available. This was an astonishing finding. Inglehart checked repeatedly, but this was what the data were reporting, and various other measures of religiosity showed similar patterns. He followed the rule “Listen to what the data are telling you, even if it surprises you.” The idea that the data itself might be wrong did not cross his mind; it had been collected by one of the world’s best-known and most reliable fieldwork organizations (which it definitely is). In retrospect, he should have known that human error can occur even in the most reliable organizations, especially when dealing with the new and unprecedented levels of complexity inherent in the smartphone mode.

To what extent does this change the conclusions in the article and book?

Happily, none of the overall conclusions change because of these errors. After an introductory paragraph, the article summarizes its findings as follows:

A dozen years ago, my colleague Pippa Norris and I analyzed data on religious trends in 49 countries, including a fewsubnational territories such as Northern Ireland, from which survey evidence was available from 1981 to 2007 (thesecountries contained 60 percent of the world’s population). We did not find a universal resurgence of religion, despiteclaims to that effect—most high-income countries became less religious—but we did find that in 33 of the 49 countries we studied, people became more religious during those years. This was true in most former communist countries, inmost developing countries, and even in a number of high-income countries. Our findings made it clear that industrialization and the spread of scientific knowledge were not causing religion to disappear, as some scholars had once assumed.

But since 2007, things have changed with surprising speed. From about 2007 to 2019, the overwhelming majority of the countries we studied—43 out of 49—became less religious. The decline in belief was not confined to high-income countries andappeared across most of the world. Growing numbers of people no longer find religion a necessary source of support andmeaning in their lives. Even the United States—long cited as proof that an economically advanced society can bestrongly religious—has now joined other wealthy countries in moving away from religion. (Inglehart, “Giving up on God,” pages 110-111).

This summary of the sudden reversal of global trends in religiosity remains completely accurate. Not a word needs to be changed. However, the subsequent discussion of the American case does need revision:

The most dramatic shift away from religion has taken place among the American public. From 1981 to 2007, the UnitedStates ranked as one of the world’s more religious countries, with religiosity levels changing very little. Since then, the United States has shown the largest move away from religion of any country for which we have data.”(Inglehart, “Giving up on God,” page 112)

As noted, the original version of the 2017 U.S. data substantially overstated the degree to which the importance of God had declined among the American public. Instead of reading “Since then, the United States has shown the largest move awayfrom religion of any country for which we have data,” it should read: “Since then, the United States has shown one of the largest moves away from religion of any country for which we have data.”

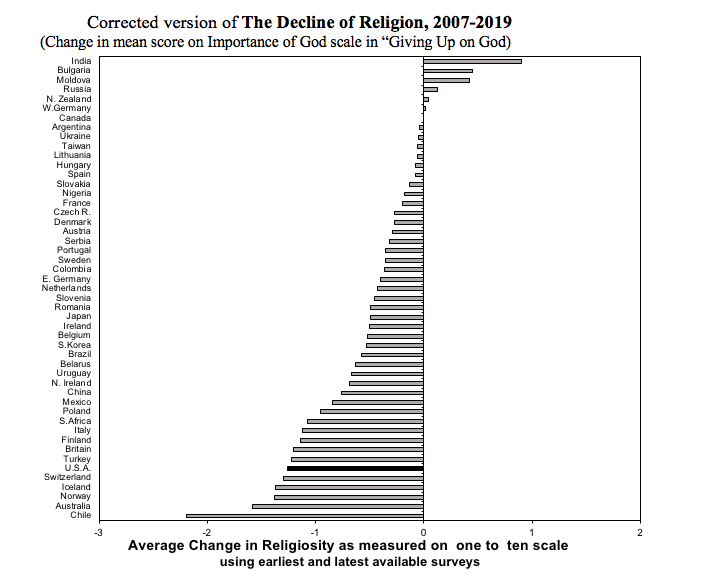

Here is a corrected version of the graph that appeared on page 113 of the Foreign Affairs article and in the book:

After decades of serving as the key example of a high-income country that had not secularized, since 2007 the American public has shown one of the highest – though not the very highest – rates of secularization found in any country for which substantial time series data are available. Responses to a question about the importance of religion in one’s life show a similar pattern, with the American public showing the fourth largest amount of secularization to be found among these 49 countries.

The corrected dataset contains numerous small changes, mostly of less than one percent. The largest of these changes involves responses to the question “Do you believe in God?” As recently as 1999, only 4 percent of the U.S. public said that they did not believe in God, but in the 2011 WVS survey the figure had risen to 11 percent. The corrupted 2017 U.S. data indicated that the figure had risen from 11 percent to 22 percent but the revised data indicated that the figure actually had risen from 11 percent to 18 percent. The difference is not enough to change the interpretation.

The item concerning “The Importance of God in your Life” shows by far the largest change of all. The corrupted version was way off – but it was off in the right direction, so the description of changing religiosity in the U.S. needs to be toned down but not reversed: since 2007, the U.S. has shown one of the largest moves away from religion in any country for which long-term time series data is available.

Some lessons for the future

We share this error report with the WVS community to increase awareness of the changes that are occurring with the widespread use of smartphones by survey respondents. In the 2017 U.S. WVS survey, 42% of respondents used a smartphone. The proportion of smartphone users have been increasing substantially in recent years and many analysts believe that this many become the dominant response mode in the near future in many societies.

The first lesson from our experience is that long surveys such as the WVS will become increasing problematic in a smartphone mode. Miller and Don Dillman tested the 2017 U.S. version of the WVS on smartphones and found that the 400 screens required over an hour for completion. As more respondents in more countries elect to use a smartphone for survey participation, it is necessary to re-think the length of our current instruments and the implications for data quality of an hour-long experience on a small screen.

The second lesson is that the coding for any survey on a smartphone is more complex than our traditional coding and the integration of different modes of data collection require thought and careful checking.

The final lesson for questionnaire writers is that we need to try to limit the wordiness of our questions. Authors of surveys that accept smartphone respondents should insist on pilot testing their instruments to see if they can read and understand each question when it is reduced to a small screen. It is an interesting experiment in reality therapy.